On average, 191 million people watched the 64 World Cup matches in 2018. [1] Since the turn of the millennium, every World Cup final has been watched by more than a billion people worldwide. In 2018, FIFA proudly announces that more than half of the world’s population tuned in. [2] For this figure, one is human only from the age of four, but 3.572 billion is still impressive. Even if the international audience is based on a sum of more or less accurate extrapolations, it can be said with high confidence that the World Cup finals are the worlds most watched recurring events. The volatile audience numbers of the Olympic opening ceremony can only compete in good years, and the short-lived hypes surrounding public figures like Lady Diana, Michael Jackson, and Mohammed Ali pale in comparison to FIFA’s cumulative attention. National sports federations such as the north-american NBA, the british Premier League or the indian IPL can boast even higher cumulative viewership due to the sheer number of matches, but none of them are as good at reaching across national borders as the football spectacle is for just over a month every four years. At the same time, the number of spectators is distributed as evenly across humanity as is otherwise only the case with the Olympics. The World Cup thus has something inherently cosmopolitan about it.

One would think that political elites around the world dedicate their resources to improve domestic living standard or forge international standing. But the gradual advance of socioeconomic indicators such as the HDI suffers from a weakness in public relations. News about the decline of illiteracy, homicide or corruption simply don’t have the same resonance as the first steps in space, private affairs of the royal family or indeed a successful performance in a global sporting event. The fact that the media dominance of the World Cup is able to keep even controversial policies off the headlines has become common practice in many places. [3] This dominance makes the World Cup a potential ingredient in any countries state-building and propaganda strategy.

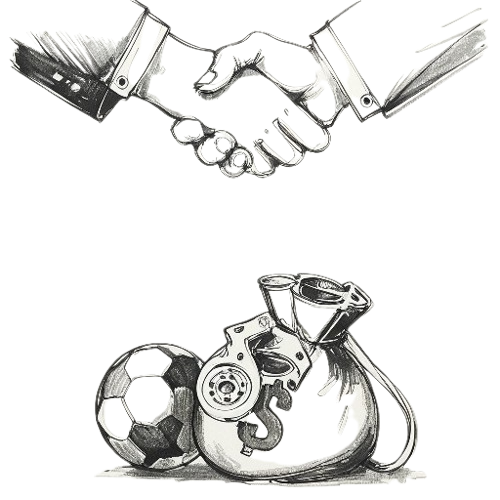

Unsurprisingly, there is a fierce battle to make an appearance on this stage. On the one hand, this involves allocating financial resources to stimulate football culture, expand the player pool and promote talents. On the other hand, it’s also about becoming effective beyond football as a sport. The most straightforward solution: Bring the World Cup to your own country. This is easier than expected, since FIFA practices a certain orthodoxy with its tradition of corruption. Of course, it must be acknowledged that it is indeed an organizational challenge to immunize high-profile decisions like this against external influences. But as long as the names of the 207 representatives of the national football associations are public and the vote is held in secret, it can be said that corruption is enshrined institutionally.

The extent of corruption of this particular World Cup is difficult to measure, and it may well be that future revelations will numerically dwarf those of previous hosts. The overripe debate about whataboutism has taught us that criticism can be justified even in absence of context. At the same time, however, we must be aware that media prominence is very much linked to politics outside of FIFA and football. Secret agreements and transactions were already proven in the case of the awards to Japan and Korea in 2002 [4]. Germany in 2006 [5] and South Africa in 2010 [6]. All of which were treated with little scrutiny by the media. When it was “time to make friends” in Germany or we “got together” in Japan and South Korea, the systematic deficiencies of the world’s football governing body receded into the background. There is a simple explanation for this: No justification was needed for the choice of host countries. Japan and Korea were the rising stars of Asian football. They always flew in front of the Asian pack in the flying geese paradigm and translated their economic emergence onto the pitch. Early on, those nations players were well known in Europe’s top leagues, and popularity ratings in global opinion surveys consistently ranked them highly. There was simply no reason to put a magnifying glass over a failure of FIFA and where no questions are asked, answers rarely come.

Eventually, however, FIFA went along with a larger international trend and echoed the trajectory of the world’s economic center. The BRICS had become political heavyweights after the world financial crisis. Billions of people become spectators and consumers. Whether the words “yielded”, “convinced”, “blackmailed”, “bribed” or “outwitted” best describe the outcome of the bidding process should be left to investigative journalism and digital forensics. What is clear, however, is that the cozy gathering of politically like-minded OECD members and their “backyard” is stirred up. Whereas people used to get together to cement the slogans, symbols and ideologies of the political status quo, the World Cup in Russia has brought a clash of opinions and their corresponding “facts”.

This course of events is taken to the extreme, with the award to Qatar. The question of corruption is at hand as never before: Besides Money there’s simply not much Qatar could have offered FIFA. Apart from likewise purely monetary matters, the small Emirate offers no football history, no narrative of politically legitimate rise known in the West, not even the necessary infrastructure at the time of the host-announcement and, to make matters worse, climatic conditions that force rule changes or a Winter-World Cup. Suddenly a system whose vulnerabilities were known and acknowledged in the Western European and North American media is presented as a corpus delicti of spreading autocrats. And with our knowledge of the political impact of such events, we have to say: For a good reason. With the World Cup, those countries that protest loudly are losing another institution of political and cultural consolidation. Already the Olympics became an uncomfortably balanced competition and the Oscars also seem to have loosened the leash of geopolitical power projection. “What the hell was that all about? We got enough problems with South Korea with trade and on top of it, they give them the best movie of the year.” Trump comments after Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite was awarded the prize in February 2020. [7] With the FIFA World Cup, the most anticipated of all cultural attractions now threatens to have its indisputability disputed.

One might think that the location is negligible, since slogans, symbols and interpretation are non-geographical values that can be constructed by oligopolistic gatekeepers and agendasetters from a distance. However, this underestimates substantive capabilities that accompany being a host. The mere presence of the unsaid but nevertheless known resistance becomes a veto of all those stories that have been told for decades without being challenged. The vacant positions are replaced by ungoverned political topics. Gianni Infantino argues that Europe should dwell in silent guilt for 3,000 years before addressing the human rights situation elsewhere [8], the palestinian flag and Keffiyeh are in great demand among fans in the Qatari stadiums [9], the German protest against the ban on the One-Love armband is answered with painful memories of the unworthy resignation of the former part of the “Mannschaft” Mesut Özil [10], and Morocco’s surprising success has been woven into the discourse of the postcolonial emergence of the global south by non western-media. [11] [12] Surprisingly little, however, was heard about the deceased guest workers who had built the splendid spectacle. The blue and yellow reminder of the war in Ukraine was also unusually modest for Western eyeballs. At the match between Uruguay and portugal, the removal of a pitch invader with messages in support of the Ukraine and Iranian women became a symbol of those issue’s medial non-existence.

All these debates deserve a profound examination and differentiated discussion. A standard that is not met by this article’s dimesnion and my lack of expertise. However, there is no intention here to evaluate the moral validity of the various patterns of argumentation. Merely their presence in the media is noted. The focus is on how topics are assigned to or withdrawn from public relevance, and how associations between topics are created and removed. After some background has been given to the political-scientific considerations on the matter we now come to my delicate opinion: I believe it is a positive development that states of various regime types can become participants and hosts of cultural spectacles such as the World Cup. Therefore, three lines of argumentation are presented in the following. For me, these arguments outweigh the already extensively discussed counter-arguments. But this should not be seen as a devaluation of these arguments. There is no doubt that the World Cups 2022 has subtly legitimized authoritarian regimes and their systematic violations of human rights, devalued football as a sport and its institutions through their financial infiltration, and cynically ignored the grievances of migrant workers, women and the Emir’s geopolitical agenda.

For my arguments, I try to consistently extrapolate the political trajectory, we had to persue, if we prohibited States like Qatar from applying as hosts. A premise of this argument is that such exclusion would only be viable by incorporating political criteria into FIFA’s host selection policy. I try to answer the following questions: What would be a logical consequence if all those states that are regularly accused of human rights violations in continental Europe and North America were deprived of the right to be part of the world cup? What reaction would we have to expect in this case? Simply put, what would be the end result of a chain of decisions that would be triggered? The answer does not come without speculation, but here I want to make an attempt…

1.

Fragmentation instead of Deplatforming

Clearly, the political significance of sport and, in particular, the international display of soft power is great enough not to put a final end to the event in case of an exclusion. It would be a constriction of the range of possibilities, but the media and political power of neither party does extend far enough for a single state to be completely isolated. Qatar and other excluded states would have to join to satisfy the societal and political need which was already cultivated for decades. It is clear that the outcasts would be equally exclusive, following the call of reciprocity, and thus one would quickly find a tidy bipolarity or even more fragmented competitions. This would not only mean the end of a cosmopolitan mass event, but also lack effective results as Qatar has political willpower and ressources to establish a paralell structure. Just as China’s exclusion from the International Space Station fostered a domestic Chinese space program within a decade [13], deplatfroming would not diminish the intensity of cultural influence of the excluded, but only its geographic reach. The countries where encounters on the pitch would be prevented could possibly be saved from their invisible influence, but the countries that would play in the excluded regimes World Cup and it’s friends would be incomparably more under the influence of those whose influence is supposed to be contained. Neither side should be overconfident about the occurrence of this case, because the borders along which this division would take place are by no means predetermined. Conceivable would be the loss of the entire continental associations of Africa and Asia together with the 77 percent of the world population inhabiting them. Exclusion would thus be fragmentation, potentially isolating a large part of humanity in the cultural sphere of influence of the excluded. Deplatforming should therefore not be treated as if anyone owned the remote control of global television. In the end, one’s own channel could be muted by mistake.

2.

Echochamber Consolidation

Policy decisions such as deplatforming are multi-effective and encounter a body of unpredictable ramifications and side effects. That means that the area in which a potential exclusion is supposed to be effective cannot be isolated. A WM exclusion would also mean an exclusion of the Qatari narrative among the remaining participants. This would cut off another channel of communication and further monopolize the corridor of conformism. The 2022 World Cup irritated the overwhelming interpretive structures of the political status quo of all parties involved. It is the small edges that do not fit into the universal template that break up the resilient misunderstanding and disregard for other countries’ political-cultural characteristics. The World Cup in Qatar has shown many that opinions can be far apart. The perceived consensus of our media by no means has a (legitimate) claim to represent the world’s population. International cultural events blur filter bubbles, by attacking the undercomplexity of one-dimensional attributions to everything and everyone. Qatar may be a monarchy, constitutionally endorse religious beliefs, and finance a significant portion of its wealth with gas exports. But anyone who thinks Qatar is just a fundamentalist oil monarchy has neither the competence to criticize nor to cooperate – both of which would be needed. And don’t get me wrong, this is not to say that everything should be covered up in the great relativism and that all political systems should be evaluated equal in terms of morality. If I could realize my personal utopia in other states with a snap of my fingers, the discussion would be obsolete in a few seconds. But it doesn’t work that way, and pure pragmatism should lead states to make gestures of respect and cooperation.

3.

Finding Morality in Pragmatism

Political elites worldwide have understood the game of nation-building. Scientific articles on the creation and sabotage of perceived legitimacy are in high demand and freely available. The Cold War and the partly peaceful overthrows of the post-Soviet and Arab worlds have produced so much training data on state collapse that the internal dynamics of regime-threatening mobilization can be identified and disrupted at an early stage. Political change can hardly be evoked in this way any more, and even when it is, its outcome has all too often been determined by opportunistic strongman and contradictory foreign interest. By contrast, the opposite strategy has proven much more productive. Political-cultural exchange gently shifts the Overton Window of those in power, and institutional and economic exchange raises the stakes in the event of conflict. These resources are what drives change in consolidated regimes such as Qatar. Qatar has reformed the Kafala system in 2020, introduced a minimum wage for migrant workers, universities are filling up with women, and freedom of choice in lifestyle is expanding. [14] [15] This development should not be mistaken for the immutable course of time – these are political decisions, which have been implemented in order to keep criticism at bay. Criticism that would not exist if Qatar were nothing more than an oil-sheikh. (Many journalists rarely distinguish between oil and gas). For this, the reflex of fundamental criticism should be abandoned. Mao’s China, the Burmese military junta, and the emirate of Qatar are dictatorships. we have scientific definitions to back this up. But what does this mean in the end? What recommendation does this expression give to three vastly different nations? We often get stuck at this level of criticism and lose the opportunity to exert pressure on tangible policies. Abstract ideologies such as freedom and democracy are as easy to dismiss as they are to fabricate. however, it becomes much more difficult when good arguments against the kafala system are presented. We should therefore devote our energy to find these items, to understand them, to formulate appropriate criticism, and, along the way, to cultivate a relationship that catalyzes openness to the concern.

4.

Harmless Channel of Conflict

Finally, I would like to recall a body of research which, during and after the cold war, asked the question whether cultural and technological subconflicts of this dipolar confrontation were contributing to the absence of a military conflict. Spacerace, the Olympics, chess – hardly any area of society was left untouched by the constant attempt to demonstrate ones systemic superiority. Beyond the Cold War, this pattern of interpretation is also underlying diplomacy. Here, the summoning, expulsion and replacement of ambassadors is supposed to send delicate signals that could otherwise only be communicated with far-reaching policies. The World Cup could also provide such a substitute function. Tariffs, sanctions, and institutional defection could become less popular when political identity is already propagated by informal sideswipes at cultural Events. Of course, it no coincidence that the anti-political measures of FIFA on Qatari soil are better at sorting out Ukrainian flags than those of Palestine, but in this way the need to express the assessment of the two conflicts can be satisfied. Now, one might think that there are already enough options for this purpose with press briefings or the general assembly of the United Nations. However, the World Cup is preferable to these options in two respects. First, the means of expression are less formalized and political elites are often only indirectly responsible for sensitive messages. Second, it reaches beyond political elites to the mass of humanity. This is especially important because criticism of the outside always includes praise of the inside. Others are only as authoritarian as one is democratic, only as backward as one is progressive, and only as militaristic as one is peace-loving. Every political elite depends on the reversal of this criticism and will use all possible platforms for it. Even hosting the World Cup is such a platform, and unlike many other ways of making a point, the quality of life of thousands of people does not have to be compromised.

For me, the World Cup is especially in the case of a host nation outside the confined circle of legitimate regimes an important irritation of the far too simple world views of distant echo chambers. Because of its civic reach, it is a valuable platform of politically effective criticism. Dealing with this critique is a dance on a fine line, because it must simultaneously grasp the complexity of our world and call out what is simply wrong. In this way the World Cup can be a contribution to international understanding and much-needed international cooperation.

[1] FIFA; 2018; More than half the world watched record-breaking 2018 World Cup.

[2] FIFA; 2018; 2018 FIFA World Cup Russia – Global broadcast and audience summary.

[3] Durante, Ruben & Djourelova, Milena; 2019; The politics of distraction: Evidence from presidential executive orders.

[4] Hughes, Rob; 2002; A corruption scandal looms over global tournament: Soccer chiefs play political game.

[5] Spiegel International; 2015; Germany Appears to Have Bought Right to Host 2006 Tournament.

[6] Esposito, Chance; 2016; A Red Card for FIFA: Corruption and Scandal in the World’s Foremost Sports Association.

[7] Ho, Vivian; 2020; Donald Trump jabs at Parasite’s Oscar win because film is ‘from South Korea’.

[8] Sky News; 2022; World Cup 2022: FIFA chief Gianni Infantino hits out at Qatar criticism saying European countries should instead ‘be apologising for the next 3,000 years’.

[9] Gebeily, Maya & Bruneau, Charlotte; 2022; Analysis: At Qatar World Cup, Mideast tension spill into stadiums.

[10] Fahey, Ciarán; 2022; Qatari fans hit back at Germany by recalling Özil in protest.

[11] Alsaafin, Linah; 2022; How Morocco gave people from Global South the power to believe.

[12] Ghosh, Rudroneel; 2022; It’s Not Just Football: Morocco’s win over Spain at Fifa World Cup is symbolic of the rise of Africa and the Global South.

[13] Baker, Sinéad; 2021; 3 astronauts arrived at China’s new space station, which it’s building as it’s banned from the international Space Station.

[14] Siccardi, Francesco; 2022; Has the World Cup Changed Qatar?.

[15] Gulf Times; 2019; About 67% of Qatar’s higher education graduates are woman.

© all rights reserved | 2024 | privacy policy | contact